Cardiomatics has been live for 8 months now. And the question we are very often asked is “How good is your automatic interpretation comparing to that of a physician/the competition?” I spent a couple of years in academia so I feel entitled to answer, “It depends.” Let me elaborate; I am pretty sure that some of these conclusions may be useful to anyone selling AI-based solutions.

Methodology

Basically, there are two ways to check how good your algorithm is.

- You can run publicly available data through your algorithm.

- You can allow someone to run their data through your algorithm.

In both cases, some kind of overall statistic (e.g. sensitivity of atrial fibrillation detection) is produced.

Magnetic Tapes and Missing Data

The advantage of the first approach is that you don’t need to share any part of your algorithm with other parties. Basically, download/purchase the data, run it through your software and publish the results. Then anyone (i.e. customers, researchers, regulators) can compare you with the state-of-the-art solutions or the competition. This approach is used during CE or FDA marking. Of course there is a risk that some manufacturers will overfit their algorithms for better results on reference databases while obtaining poor results on real-life data. The other challenge is the data itself.

There are two basic databases which are used to validate ECG algorithms:

- the AHA Database for Evaluation of Ventricular Arrhythmia Detector

- the MIT-BIH Arrhythmia Database

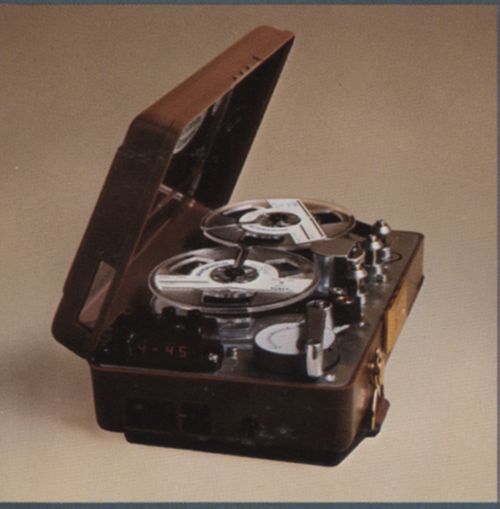

They were both recorded 40 years ago with devices like this:

- tape sticking,

- tape slippage,

- small variances in the orientations of the tape heads.

I am not saying that the MIT or AHA databases are worthless. They made the development of first ECG analysis algorithms possible in the 1980s and 90s. And the annotation itself is very good. For example, the MIT database consist of 109,000 beat labels. And from the beginning it has been amended only 23 times.

You think that magnetic tapes are funny? Listen to this: when we purchased the AHA database we expected 80 recordings (8 test cases and 10 files in each). But on the CD that came in the mail here were only 79 files. We asked about the missing file. Here is the official answer:

The ECG data was acquired in the late 1970s and early 1980s by a working group of the AHA. The working group was dissolved long ago and I doubt that anyone at the AHA today will have any memory of this project. Initially the 4.19 GB of data was stored on a large number of magnetic tapes, which was the only viable storage media at that time. Unfortunately, about 20 years ago, one of the test files was corrupted and could not be recovered. The data is no longer available and cannot be recreated.

Bottom line? It is like benchmarking 3.0 GHz CPUs by playing “Mario”.

May the Best Win!

The second approach comes from academia. You make your MATLAB/Python/whatever code available, and anyone who owns ECG data can compare it with his solution. You can also publish a paper with a mathematical description of your algorithm so someone could reproduce your results. Imagine that customer could run his 1,000-ECG database through your algorithm and a competitor solution. May the best one win! There are only two problems with that.

While it is in the DNA of a scientist to publish results, business DNA dictates that one protect intellectual property. There is huge risk in allowing someone else to run his data through your algorithms. The biggest, of course, is that someone will duplicate your code. Even if you somehow reduce this risk (e.g. via well-protected API, or code obfuscation) there is a risk of reverse engineering.

But even if we take that risk there is another challenge – reference. Cardiologists spent weeks (months?) annotating the AHA and MIT database so the results could be compared with this golden standard. One needs to have an annotated database in hand to make this happen. And, to be honest, none of our customers have had that kind of resource.

Give AI a Try

Here is how we deal with this impasse. We encourage customers to implement Cardiomatics in their organisation. It is a simple and low-cost step. Then, for a couple of weeks, they run it head–to-head with their current processes (manual or semiautomatic interpretation). Afterwards, they compare the results obtained from us with those coming from clinicians. And we have not had a situation in which they were not satisfied.

And please don’t be mad at us when our answer to the question “How good are you, compared to the competitors?” comes back as “It depends.”